Pause for a moment and look around at your digital world. The mouse under your hand, the multiple windows open on your screen, the ability to jump between related ideas with a click, or even the seamless collaboration tools that connect you with colleagues across the globe. These feel like fundamental parts of computing, don’t they? But nearly sixty years ago, these weren’t commonplace; they were radical, almost unbelievable ideas. They were part of a single, live demonstration that laid out a blueprint for the digital age long before most people even knew what a computer was. This wasn’t just *a* showcase; it earned the legendary title: the ‘Mother of All Demos’.

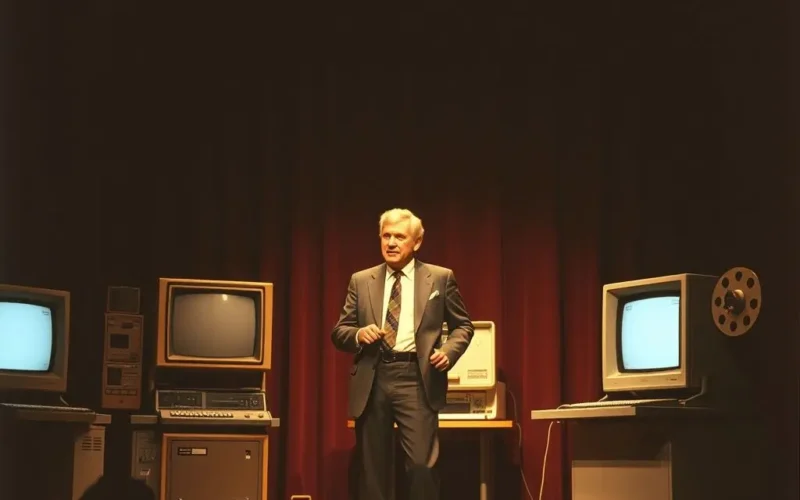

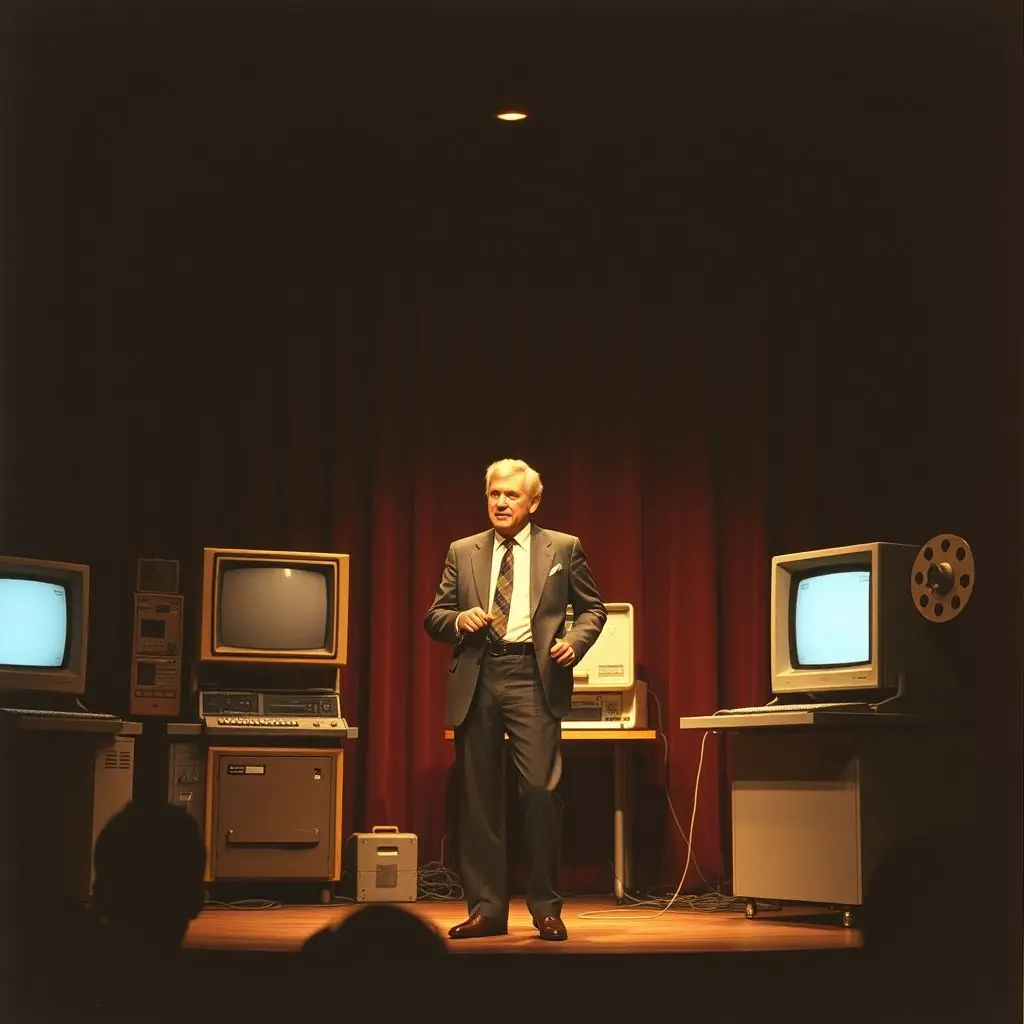

On a chilly afternoon, December 9th, 1968, in San Francisco, a visionary named Douglas Engelbart stepped onto a stage at the Fall Joint Computer Conference. What followed was a 90-minute live presentation that would become one of the most pivotal moments in the history of technology. Engelbart, director of the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), wasn’t just showing off new gadgets; he was demonstrating an entirely new paradigm for how humans could interact with computers and, more importantly, with information and each other.

This wasn’t just a talk; it was a live, interactive system demonstration called the oN-Line System, or NLS. Engelbart and his colleague Jeff Rulifson, located miles away at SRI, collaborated on screen in real-time, connected by a custom-built modem and microwave link. Imagine the sheer audacity of this in 1968!

Table of Contents

What Made It The “Mother of All Demos”?

The reason this demo is lauded so highly is the sheer number of foundational technologies showcased in one go. It was a dazzling parade of concepts that would take decades to become mainstream. Let’s break down some of the most impactful elements:

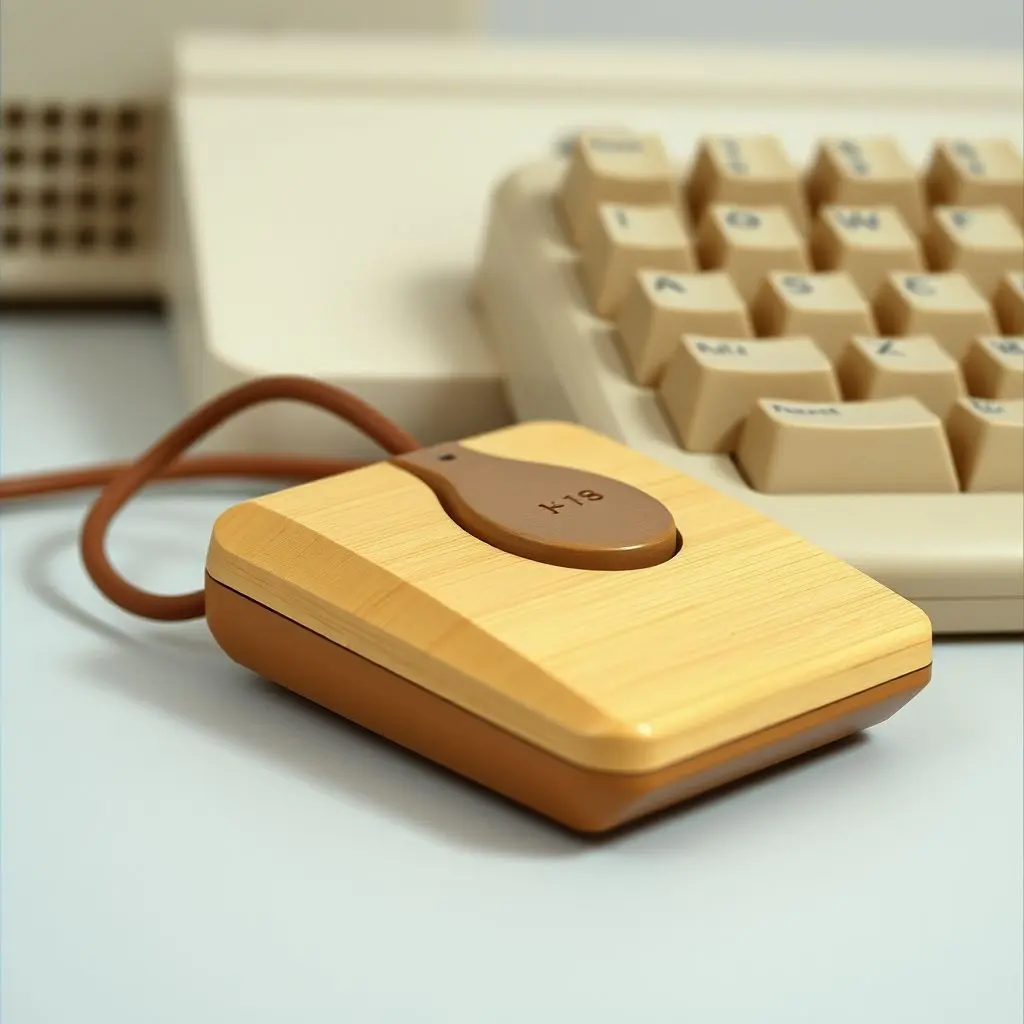

The First Computer Mouse

Perhaps the most tangible innovation revealed was the computer mouse. Engelbart needed a better way to select and manipulate text and objects on a screen than using light pens or keyboards. His team developed a small wooden device with two wheels and a cord, earning it the name ‘mouse’. In the demo, he showed how this simple pointing device could effortlessly move a cursor, select text, and navigate the system. It was a concept so intuitive yet so novel at the time, forever changing how we interact with computers.

Hypertext: The Precursor to the Web

Long before Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web, Engelbart demonstrated hypertext. Users could click on highlighted words or phrases within a document to instantly jump to related information, other documents, or even specific sections within the same document. This non-linear way of organizing and accessing information was a radical departure from the sequential nature of print and traditional computing, laying the conceptual groundwork for the internet’s interconnectedness.

Windows and Multi-Pane Displays

Managing multiple tasks and information streams is second nature today thanks to windows. Engelbart’s NLS allowed users to divide their screen into multiple sections or ‘windows’, displaying different documents or parts of the system simultaneously. This enabled users to view outlines alongside detailed text, compare different documents, or keep different tools visible, dramatically improving efficiency and interaction.

Online Collaboration and Shared Screens

In a breathtaking segment, Engelbart demonstrated collaborative editing. With Rulifson miles away, they simultaneously worked on the same document, with changes appearing instantly on both screens. They also used a primitive form of video conferencing, with a small video window showing Rulifson. This live demonstration of shared digital workspaces and remote interaction was years ahead of its time, predicting the rise of tools like Google Docs, Zoom, and countless other collaboration platforms.

Interactive Text Editing (Word Processing)

Forget punch cards or batch processing. The NLS offered interactive text editing capabilities that resemble modern word processors. Users could type, delete, insert, and move text around fluidly using the keyboard and mouse. Features like structuring documents with outlines and linking elements were part of this system, making it far more dynamic than any text manipulation tools available then.

It’s difficult to convey the sheer novelty and impact of seeing all these elements working together, live, in 1968. The audience, comprised mainly of computer scientists used to batch processing and command-line interfaces, was witnessing something truly out of a science fiction novel.

If you want a quick glimpse into this incredible moment and the foresight it represented, check out this short video:

Engelbart’s Deeper Vision: Augmenting Human Intellect

It’s crucial to understand that Engelbart’s goal wasn’t just to invent cool gadgets. His lifelong work, and the driving force behind the NLS, was the concept of “augmenting human intellect.” He believed that complex global problems required humans to work together more effectively, and that technology could be a powerful tool to enhance our collective problem-solving capabilities, memory, and communication. The mouse, hypertext, windows, and collaboration tools were not ends in themselves, but means to empower humans to think, learn, and collaborate better.

The Enduring Legacy

While the NLS itself didn’t become a commercial product, its DNA is present in virtually every computing device and software application we use today. Xerox PARC researchers were heavily influenced by Engelbart’s work (many attendees of the demo later worked there), leading to systems like the Alto, which in turn inspired Apple’s Macintosh and Microsoft Windows. The concepts of linking information directly led to the World Wide Web. Collaborative software owes a direct debt to the shared screen and video conferencing demos. Engelbart’s foresight wasn’t just about predicting specific tools; it was about foreseeing a fundamentally different, interactive, and collaborative relationship between humans and computers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Doug Engelbart?

Douglas Engelbart (1925-2013) was an American engineer and inventor, best known for his pioneering work on human-computer interaction at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). His research aimed at augmenting human capabilities using technology.

What was the oN-Line System (NLS)?

The oN-Line System (NLS) was a revolutionary computer system developed by Engelbart and his team at SRI. It was designed to be a collaborative, interactive workspace for augmenting human intellect and included many features common in modern computing, such as hypertext, windows, and interactive text editing.

Why is it called the “Mother of All Demos”?

The nickname was coined years later by journalist Steven Levy due to the demonstration’s sheer scope and the large number of fundamental computing concepts that were revealed together for the first time, many of which became cornerstones of modern personal computing and the internet.

Did Engelbart get rich from the mouse?

No. While Engelbart held the patent for the mouse (filed in 1967, granted in 1970), SRI licensed it to Apple for a very low fee (reportedly around $40,000) in the early 1980s. Engelbart received no royalties from the mouse’s widespread commercial success, as the patent had expired by the time it became ubiquitous.

Was the internet shown in the demo?

No, the internet as we know it didn’t exist yet, though ARPANET (a precursor) was being developed around the same time. The NLS demo used a dedicated line for collaboration. However, the *concept* of linking information (hypertext) and remote collaboration shown in the demo were foundational ideas that would later be central to the internet’s function.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

The ‘Mother of All Demos’ wasn’t just a historical event; it was a prophecy. Engelbart didn’t just show us future tools; he showed us a future *way* of working and interacting. His vision of computers as extensions of human capability, rather than mere calculation machines, continues to resonate. Reflecting on that single presentation from 1968 is a powerful reminder that today’s ubiquitous technology stems from audacious ideas and relentless innovation aimed at empowering us. We’re still building upon the foundation he unveiled that day.