Ever wonder about the origins of that powerful lens tucked inside your smartphone? The ability to capture moments instantly, digitally, without a roll of film in sight? It feels like magic now, but this revolution had a surprising, almost unbelievable beginning. And the plot twist? It all started inside the walls of a company synonymous with film photography: Kodak.

Back in 1975, amidst the whir of film processors and the smell of developing chemicals, a bright spark of innovation ignited thanks to a brilliant Kodak engineer named Steve Sasson. He wasn’t just tinkering; he was building the future. His project? The world’s very first digital camera prototype.

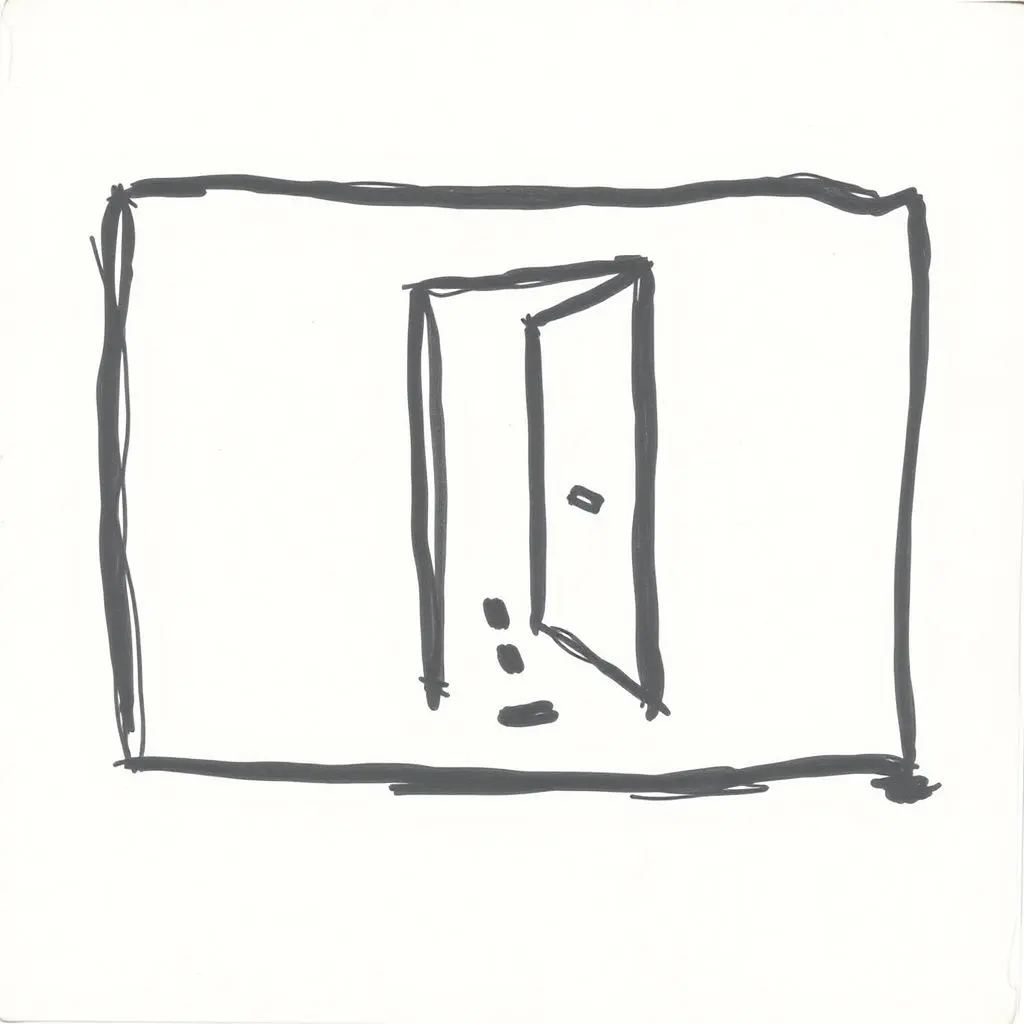

Imagine the scene: a device pieced together with parts that seem almost primitive by today’s standards. It utilized a modified Super 8 camera lens – a nod to Kodak’s existing expertise – paired with a nascent, cutting-edge technology for the time: a Charge-Coupled Device, or CCD chip. This wasn’t just a gadget; it was a foundational step into a new era of image capture.

Want a quick, visually engaging summary of this incredible story? Check out our Shorts video below:

Table of Contents

The Birth of a Revolution (Built in a Basement?)

Steve Sasson’s assignment was almost exploratory: could electronic photography be feasible? Working with technician Larry Page (not the Google one!), Sasson embarked on a journey into the unknown. Their lab was less a high-tech facility and more a basement workshop at Kodak’s sprawling Rochester, New York campus. The goal wasn’t necessarily a consumer product immediately, but rather to understand the potential of capturing images electronically.

The core of Sasson’s prototype was a Fairchild 1024×1 element CCD line sensor. Unlike modern sensors that capture a whole image at once, this was a linear sensor, meaning the image had to be scanned line by line. To do this, Sasson modified a Kodak Super 8 movie camera body and lens. Light passed through the lens and hit the CCD line sensor.

But capturing the light was only half the battle. Where did the image go? There was no internal flash memory or SD card. Sasson’s ingenious solution involved a portable digital cassette recorder. The electronic data from the CCD was converted into digital information and written onto a standard cassette tape.

This groundbreaking device wasn’t fast. It took a staggering 23 seconds from the moment the button was pressed to record a single, black and white image. And the resolution? A minuscule 0.01 megapixels (10,000 pixels), roughly 100×100. To view the image, the cassette tape had to be played back on a custom-built digital cassette player, which then displayed the image on a television screen. The quality was low, the process slow, but it worked. It was proof of concept.

Sasson and his team had essentially invented the core principles of digital photography: converting light into electronic signals, digitizing that information, and storing it electronically.

Presenting the Future: Kodak’s Reaction

Armed with their working prototype, Sasson and his colleagues demonstrated their invention to Kodak executives in 1976. This wasn’t some minor internal project; this was a fundamental shift in how images could be captured.

How did the leadership of the world’s dominant photography company react to the device that held the key to the future?

With a mix of awe and profound fear.

They understood the technology. They saw its potential. But more vividly, they saw the threat it posed to their colossal, immensely profitable film and photographic paper empire. Kodak wasn’t just selling film; they were selling the entire process: the cameras that used film, the film itself, the chemicals to develop it, the paper to print photos, and the machines in photo labs. This intricate ecosystem generated billions.

A filmless future was, to them, an existential crisis. It was the ultimate innovator’s dilemma laid bare: embrace a disruptive technology that could cannibalize your core business, or protect the cash cow and hope the disruption doesn’t happen too fast.

The Golden Goose vs. The Digital Duckling

Kodak chose the latter. They decided, essentially, to keep the technology under wraps. They weren’t blind; they continued research and development in digital imaging, accumulating patents. Steve Sasson himself went on to work on other digital projects within Kodak. But the company’s public face, its marketing, its primary business strategy, remained firmly anchored in film.

They feared digital would kill their golden goose (film), and they couldn’t process the picture of a future where their main product was obsolete. They developed the future of photography but lacked the foresight to develop a business model to embrace it.

This decision, driven by short-term profit protection, would prove to be one of the most infamous examples of corporate misjudgment in history. While Kodak sat on its groundbreaking invention, other companies, many from the electronics sector rather than traditional photography, began investing heavily in digital technology throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

The Unfolding Picture: The Digital Age Arrives

As digital technology improved, cameras became smaller, faster, and captured higher resolutions. Storage moved from cumbersome cassettes to floppy disks, then to memory cards. The internet allowed for easy sharing. The convenience, speed, and declining cost of digital imaging rapidly eroded the advantages of film for everyday photography.

Kodak, despite its foundational role in creating digital photography, was slow to pivot. Its digital camera offerings initially lagged behind competitors, and its core film business plummeted. The company that invented the technology that defines modern photography ultimately filed for bankruptcy protection in 2012, a stark, ironic end for a once-invincible giant.

While Kodak emerged from bankruptcy focusing on commercial imaging and printing, its story remains a powerful cautionary tale about the perils of failing to embrace disruptive innovation, even when it comes from within your own labs.

Steve Sasson’s prototype, now a historical artifact at the Smithsonian, stands as a testament to human ingenuity and the potential of electronic imaging. It also serves as a physical reminder of the difficult choices corporations face when their past success clashes with a disruptive future.

FAQs About the First Digital Camera

Q: Who invented the first digital camera?

A: The first working prototype of a digital camera was invented by Steve Sasson, an engineer at Kodak, in 1975.

Q: When was the first digital camera invented?

A: Steve Sasson completed the prototype in December 1975.

Q: How did the first digital camera work?

A: It used a Super 8 camera lens, a Fairchild 1024×1 pixel CCD line sensor, and recorded black and white images onto a standard digital cassette tape. It took 23 seconds to capture one image.

Q: What was the resolution of the first digital camera?

A: It had a resolution of 0.01 megapixels (10,000 pixels), roughly equivalent to 100×100 pixels.

Q: Why did Kodak hide the invention?

A: Kodak feared that digital photography would destroy their highly profitable business based on film, photographic paper, and processing chemicals. They chose to protect their existing market rather than fully embracing the disruptive technology.

Q: What happened to Kodak because of this decision?

A: While Kodak continued digital research, their reluctance to aggressively market consumer digital products allowed competitors to dominate the emerging market. Their film business declined rapidly, ultimately leading to Kodak filing for bankruptcy protection in 2012.

Looking Back at the Digital Dawn

The story of the first digital camera is more than just a technical achievement; it’s a compelling business case study. It highlights how difficult it can be for established companies to adapt when their core identity and revenue streams are threatened by innovation. Kodak had the visionaries and the technology, but the fear of change prevented them from developing the business model needed to lead the digital age they themselves initiated. A truly fascinating chapter in tech history.