Okay, let’s ponder one of the more abstract, yet strangely fascinating questions out there: How much does the entire internet actually weigh? Not the servers, not the cables snaking across the ocean floor, not your phone or computer. We’re talking about the data itself, or rather, the physical manifestation of the energy powering it at any given moment.

It sounds like a philosophical riddle, right? Billions of websites, trillions of videos, an unfathomable ocean of information… surely, that must have some serious heft?

Prepare yourself for a factoid that might just reboot your understanding of the digital realm:

Table of Contents

The Mind-Bending Answer: Roughly the Weight of a Strawberry

Yes, you read that correctly. According to estimations that delve into the physics of energy and mass, the total physical mass of all the electrons actively engaged in storing and transmitting the world’s internet data at any specific instant is astonishingly small. So small, in fact, that its cumulative weight is often compared to that of a single, average strawberry.

It seems utterly impossible when you picture the sheer scale of the internet – all those cat videos, streaming movies, complex algorithms running simultaneously. But here’s where the crucial distinction lies: the data itself – the ones and zeros, the bits and bytes – don’t possess physical mass. Data is an arrangement, an instruction, a pattern.

Think of it like a book. The story within the book doesn’t weigh anything. The weight comes from the paper and the ink. Similarly, internet data is like the story. The physical ‘weight’ comes from the tiny, energetic particles that enable its existence and movement.

The question then becomes, what *does* have mass in this equation?

It’s Not the Data, It’s the Electrons (And Their Energy)

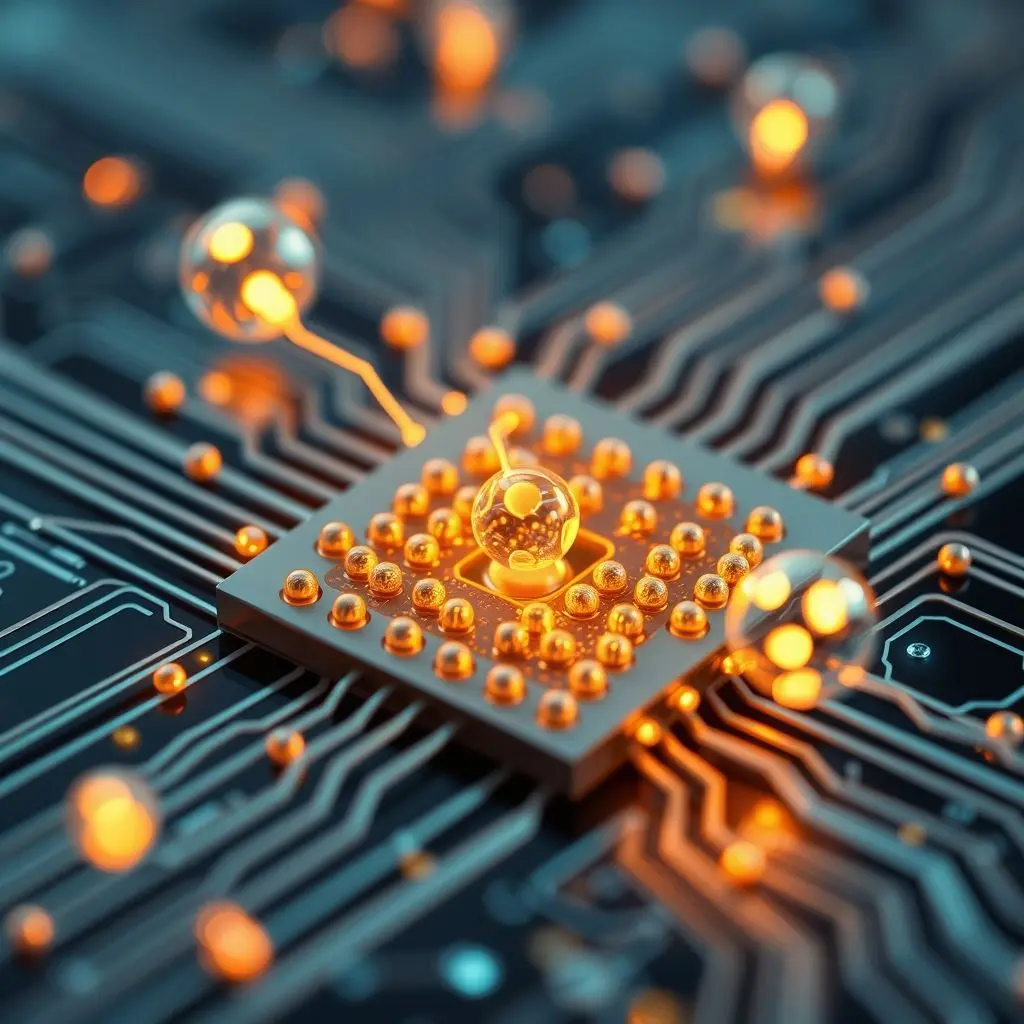

The internet exists on physical hardware: servers humming in data centers, routers directing traffic, cables transmitting signals, and the devices we use to access it. At the most fundamental level, within this hardware, information is stored and processed by manipulating the state of tiny particles, most notably electrons.

When data is stored (like a bit being ‘on’ or ‘off’ in memory) or transmitted, electrons within the circuitry are moved or energized. These electrons, while incredibly light individually, are physical particles and do possess mass.

Furthermore, these processes require energy. And this is where things get truly mind-bending, thanks to Albert Einstein’s most famous equation:

E=mc²: How Energy Adds (a Tiny Bit of) Mass

Einstein’s groundbreaking equation, E=mc², tells us that energy (E) and mass (m) are interchangeable; they are two sides of the same coin. The ‘c²’ is the speed of light squared, a very large number, which means a tiny amount of mass is equivalent to a massive amount of energy, and conversely, a massive amount of energy is equivalent to only a tiny amount of mass.

When electrical energy powers the internet’s infrastructure – lighting up circuits, moving electrons to represent data states, transmitting signals – that energy itself contributes to the total mass of the system. The electrons in their excited, energetic states (representing active data) have slightly more mass than they would in a lower energy state.

The calculation behind the ‘strawberry’ figure involves estimating the total energy being consumed by all the active internet-connected devices and infrastructure globally at any given moment and then converting that total energy figure into mass using E=mc². Alternatively, it involves estimating the number of active electrons and the minuscule increase in their relativistic mass due to the energy they possess.

Given the sheer scale of energy consumption and the countless active electrons, you might still expect a larger number. But because the mass equivalent of energy (or the mass increase of energized particles) is so incredibly small (remember the ‘c²’ factor?), when you sum up all these tiny contributions from the world’s active internet, you arrive at this surprisingly small figure – roughly the weight of a strawberry.

Important Clarifications and Nuances

It’s crucial to understand what this ‘strawberry’ weight represents and what it doesn’t:

- It is not the weight of the physical internet infrastructure (servers, routers, cables, satellites, towers, user devices, etc.). That weight is astronomical, millions of tons.

- It is not the potential mass if all the data were somehow converted into pure energy (like annihilating matter and antimatter).

- It is an estimation of the mass contributed by the energy and active electrons powering the internet *in its current operational state*.

- The exact figure can vary depending on the estimate of global internet activity and energy consumption at a specific time. Hence, ‘roughly’ a strawberry.

This concept highlights the incredibly abstract nature of the data we interact with daily. It exists as patterns of energy and electron states, with minimal physical mass impact, yet it powers a global digital economy and shapes modern life.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Internet’s ‘Weight’

Does the weight of the internet change?

Yes, theoretically, very slightly. The weight is tied to the total energy being consumed by active internet components globally. If more people are online, streaming high-bandwidth content, or running complex computations, more energy is used, meaning the tiny mass equivalent increases slightly. Conversely, during periods of low activity, the weight would decrease.

Is this calculation universally accepted?

The underlying physics (E=mc²) and the concept that active energy contributes mass are fundamental. The ‘strawberry’ figure is an estimate based on calculations by physicists and engineers attempting to quantify this effect based on estimated global energy usage for internet operations. It’s a widely cited comparison to illustrate the point, but the exact number is subject to the accuracy of the global energy consumption estimate and the specific method of calculation.

Does data stored on inactive devices (like on a hard drive that’s turned off) contribute to this weight?

Not to this specific ‘active internet’ weight calculation. Data stored statically on a powered-off device or a device using very low power (like data on flash memory when the device is off) contributes negligibly to the dynamic energy consumption and thus the E=mc² mass equivalent being discussed here. This calculation focuses on the energy of the *active* internet – the data in transit and being processed or actively held in volatile memory.

Are electrons the only particles contributing mass?

Electrons are a primary focus because their movement and energy states are fundamental to how electronic devices store and process data. Other particles are involved in the physical infrastructure (protons, neutrons in atoms making up the hardware), but this specific calculation isolates the mass contribution from the *energy* required to power the active *information processing* part of the internet, which largely involves electron behavior.

Beyond the Scale

The idea that the entire, vast, seemingly infinite internet, at any given moment, might have a physical mass roughly equal to a small piece of fruit is profoundly humbling. It forces us to reconsider the nature of the digital world we inhabit.

It’s a powerful illustration of how information, unlike physical objects, is inherently massless. The weight comes only from the physical systems and the energy required to bring that information into being and move it around.

This tiny, almost imperceptible physical footprint for something so monumentally significant is a testament to the strange and wonderful physics that governs our universe, reminding us that the most impactful creations aren’t always the heaviest ones.

Your brain might still be buzzing from this perspective shift. It’s a concept that certainly makes you look at your internet-connected devices a little differently.