Ever find yourself standing at the checkout, hearing that familiar beep as product after product is scanned? It’s a sound so commonplace, so mundane, yet it signifies a transaction powered by a tiny, striped pattern we see on virtually everything. That little pattern – the barcode – seems incredibly simple, right? Yet, its existence isn’t just happenstance. It’s a fascinating tale born from a genuine need for speed and efficiency in the bustling world of mid-20th-century retail.

Picture this: the late 1940s. Supermarkets and stores were growing, but the process of checking out customers and managing inventory was, quite frankly, a mess. Cashiers had to manually key in prices for every single item, leading to long lines, errors, and a mountain of administrative work to keep track of stock. It was slow, inefficient, and ripe for innovation.

This challenge caught the attention of two bright minds, Bernard Silver and Joe Woodland. Students at Philadelphia’s Drexel Institute of Technology (then Drexel Institute of Technology), they overheard a local food chain executive pleading with the dean for a way to automatically read product information during checkout. Inspired by this real-world problem, Silver and Woodland took up the gauntlet, embarking on a journey that would eventually revolutionize global commerce.

Table of Contents

The Early Whispers of Automation: Morse Code and Sand

Their initial brainstorming sessions were wide-ranging and creative. They weren’t immediately thinking of stripes. One early idea, reportedly inspired by Morse code, considered using ink patterns that would represent product information. Woodland, having experience with Morse code from his Boy Scout days, saw the potential in translating letters and numbers into dots and dashes, or perhaps thin and thick lines.

Another concept involved using ultra-violet (UV) ink, which could only be seen and read under special light. While intriguing, this proved impractical and costly for mass production and reliable scanning technology wasn’t readily available.

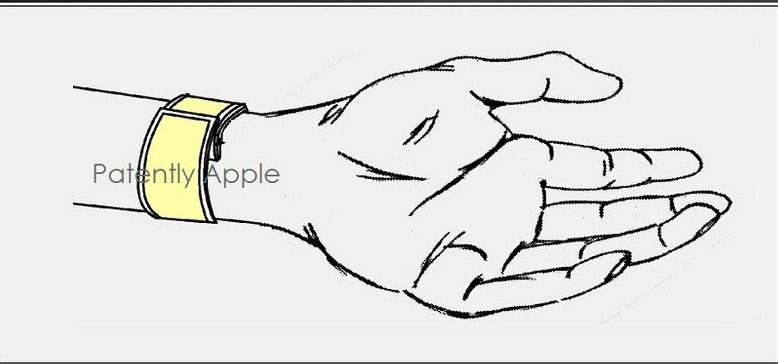

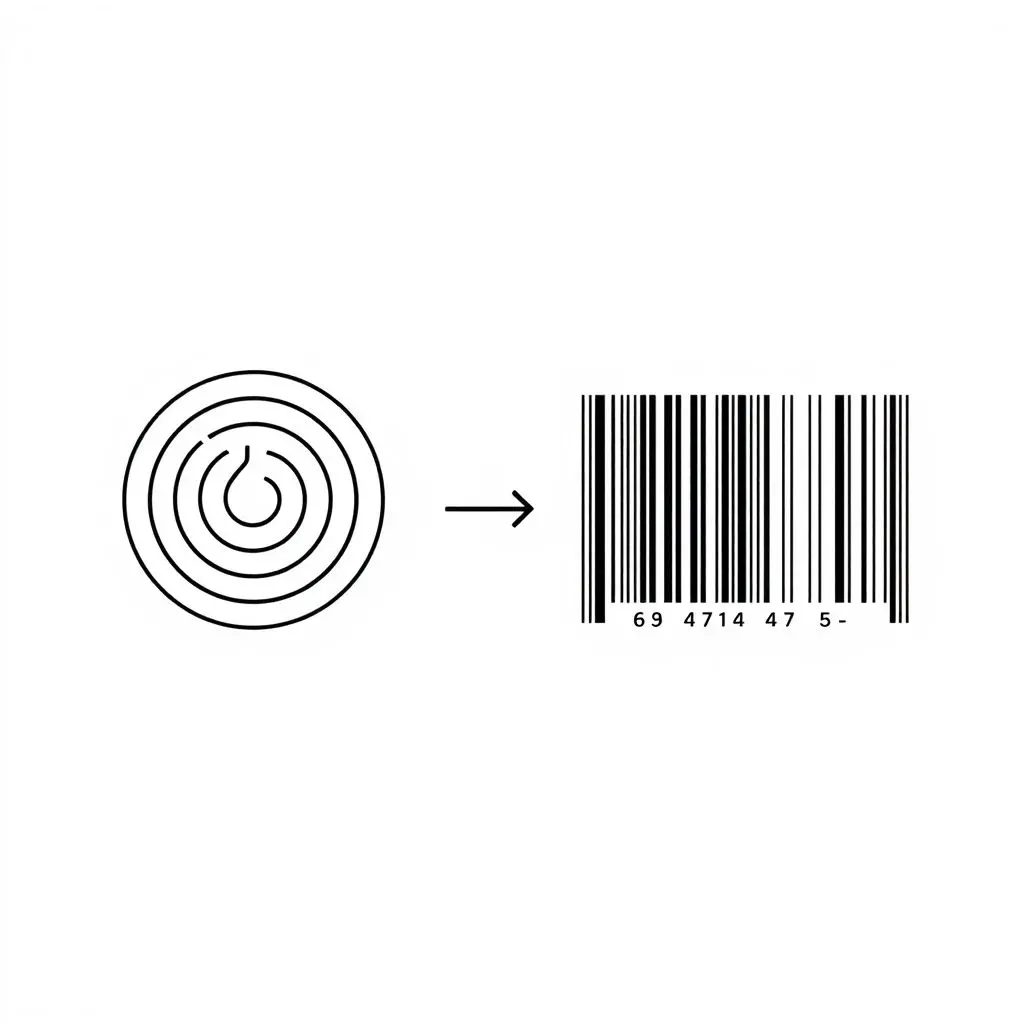

The true breakthrough moment for Woodland came later, after he left Drexel and was contemplating the problem while living in Florida. As he recounted years later, he was sitting on a beach, sketching in the sand. Thinking about how sound could be translated into visual waveforms (like on a movie soundtrack), he drew vertical lines, varying their thickness. He realised that these lines, like Morse code but arranged linearly, could encode data. This linear arrangement, readable by a simple scanner moving across it, was the core concept. He even experimented with a circular ‘bullseye’ pattern, thinking it would be easier to scan regardless of orientation, although this presented its own printing challenges later on.

Bernard Silver, meanwhile, focused on the patent application side. Together, they filed for a patent based on their linear and circular code concepts, which was granted in 1952 (U.S. Patent 2,612,994).

From Patent to Practicality: The Road to UPC

While the patent was a crucial step, the technology and industry infrastructure weren’t quite ready. The early 1950s scanner technology was expensive and unreliable. Printing the complex bullseye pattern consistently on different packaging materials also posed significant hurdles.

Over the next couple of decades, various companies and engineers chipped away at the problem. Different coding schemes and scanning technologies were proposed and tested. IBM, where Joe Woodland eventually worked, played a significant role in developing the practical application of the concept.

The real push towards standardization came in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The grocery industry, still grappling with inefficiencies, formed the Uniform Grocery Product Code Council (UGPCC) to select a single, industry-wide standard for product identification. After evaluating several proposals, they chose the linear barcode concept, largely due to its potential for reliable printing and scanning with emerging laser technology.

Key to the final design was George Laurer, an engineer at IBM. He refined the linear code design, making it robust and scannable even if slightly damaged or poorly printed. He developed the specific 12-digit Universal Product Code (UPC) symbology – the familiar pattern of bars and spaces that encodes manufacturer and product information.

Want a quick visual recap of this inventive journey? Check out our YouTube Short below:

The Beep Heard ‘Round the World: The First Scan

The moment the barcode truly arrived on the scene was June 26, 1974. At a Marsh Supermarket in Troy, Ohio, a pack of Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit chewing gum became the very first retail product to be scanned using a UPC barcode. The scanning system was developed by NCR (then National Cash Register) and the pack of gum is now a historical artifact residing at the Smithsonian Museum.

This single transaction marked the beginning of a quiet revolution. While initial adoption was slow due to the cost of scanners and the need for widespread product marking, the benefits soon became undeniable.

The Silent Language of Modern Commerce

The impact of the barcode stretched far beyond just speeding up checkout lines. It fundamentally changed how businesses operate:

- Inventory Management: Tracking stock became infinitely more accurate and efficient. Businesses knew exactly what was selling and when to reorder, reducing waste and stockouts.

- Supply Chain Efficiency: Products could be tracked from manufacturing plants to distribution centers and finally to the store shelf, optimizing logistics and reducing costs.

- Reduced Errors: Automated scanning drastically cut down on manual keying errors, improving accuracy in pricing and inventory.

- Faster Service: Checkout lines moved faster, improving customer satisfaction.

- Data Analytics: Barcode data provided invaluable insights into consumer purchasing patterns, allowing retailers to make data-driven decisions on stocking and promotions.

From a seemingly simple pattern of lines, the barcode became the silent language that underpins global retail and logistics. It’s a testament to how solving a specific, pressing problem with clever engineering and standardization can lead to world-changing innovation.

While 1D barcodes remain prevalent, the technology continues to evolve with 2D barcodes like QR codes gaining popularity for storing more complex information and enabling new interactions, but they all trace their lineage back to those early concepts born from a need for speed at the checkout counter.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Barcode

Got more questions about this ubiquitous invention?

Who invented the barcode?

The core concept was patented by Norman Joseph Woodland and Bernard Silver in 1952. George Laurer at IBM was instrumental in developing the specific UPC (Universal Product Code) symbology widely adopted by the retail industry.

When and where was the first retail barcode scan?

The first retail transaction using a UPC barcode occurred on June 26, 1974, at a Marsh Supermarket in Troy, Ohio. The product scanned was a pack of Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit chewing gum.

What does UPC stand for?

UPC stands for Universal Product Code.

How does a barcode work?

A barcode is a visual representation of data. A scanner shines light (often a laser) onto the pattern of dark bars and light spaces. The bars absorb light, while the spaces reflect it. The scanner measures the reflected light and converts the pattern into electrical signals. This pattern corresponds to a sequence of numbers (and sometimes letters). This numerical code is then looked up in a database (like a store’s point-of-sale system) to retrieve information about the product, such as its price and description.

Are there different types of barcodes?

Yes, there are many types. The most common linear barcodes are UPC (used in retail, primarily in North America) and EAN (European Article Number, similar to UPC but used globally). There are also 2D barcodes, such as QR codes, which can store much more information in a matrix pattern.

Is the barcode invention still patented?

The original patent by Woodland and Silver expired long ago. The UPC standard itself is managed by a global non-profit organization (GS1) which assigns unique company prefixes.

So, the next time you hear that familiar beep at the checkout, take a moment to appreciate the history embedded in those simple stripes – a blend of ingenuity, perseverance, and standardization that fundamentally changed the world of commerce. It’s truly the silent language of how goods move around the planet.